Faster Natural Gas Growth Means Faster Emissions Reductions According to Princeton University

The newest iteration of potential future electricity supplies released by Princeton University makes a startling observation: Electricity produced from natural gas grows fastest into the 2030s in the *Net-Zero* scenario, according to the Ivy League university’s updated modeling of U.S. emissions pathways.

The implications of this – for the U.S. economy, your personal energy bills, and the rate of emissions reductions – are all incredibly positive.

As AGA’s Richard Meyer notes, “The imminent peak of natural gas generation has been predicted for years by many forecasters. But every year, even with record renewables growth, we hit a new high in gas generation. And emissions continue to drop. Maybe the models are finally catching up.”

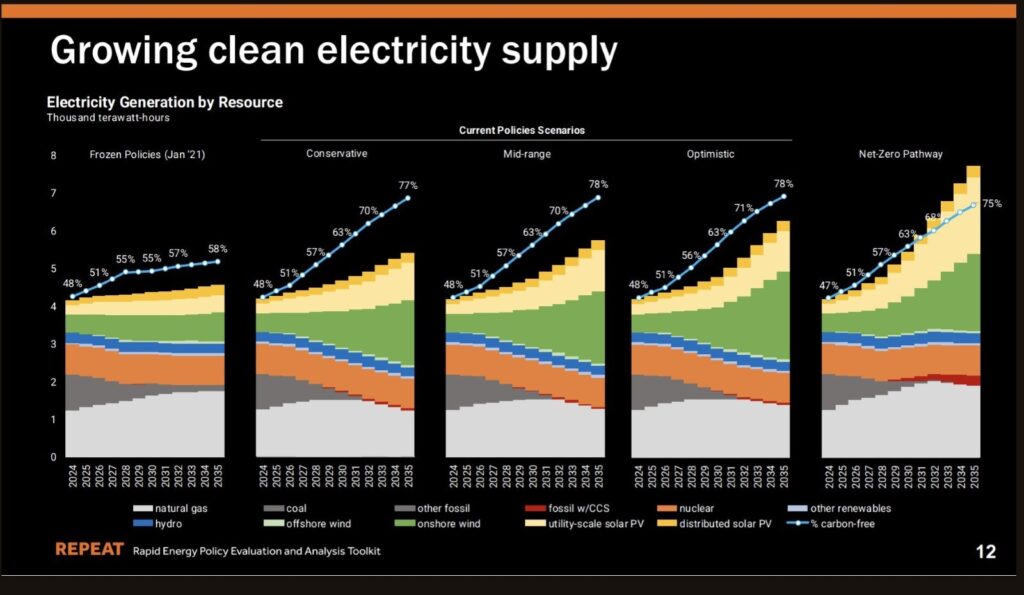

The various output of the model in question is below. Natural gas is in light grey at the bottom of each potential projection.

Interestingly, this represents a significant shift from last year’s projections. As energy policy expert Dan Byers notes, last year’s projections from Princeton saw natural gas used for electric generation declining rapidly, falling to 800 terrawatt hours (twh) by 2030 and 400 twh by 2035 – and this explicitly excludes up to 250 twh of new data center demand. It’s unclear what assumptions were updated or what changes were made to the modeling done by Princeton to cause this shift, as the underlying data is not drastically different from last year.

Reaching net-zero by 2035 is ambitious, however, as the projections above make clear, if it can be done and we’ll need quite a bit of natural gas to make it happen. There are a few reasons for that.

First, you’ll notice the dark gray section representing coal. Natural gas power generation has about half the emissions per unit of electricity that coal generation does. Natural gas can be substituted for coal in existing thermal power plants with minimal effort. The best part is that natural gas is more affordable than coal. It’s a no brainer – the easy process of switching to natural gas cuts emissions in half while lowering fuel costs. This is why you’ll notice natural gas rapidly sweeping up coal’s share of generation within the next six years in every projection.

The other main reason natural gas is so important for the net-zero pathway is that natural gas is a key partner for renewables. You’ll notice that the total amount of generation capacity deployed in Princeton’s projections is highest in the lower emissions scenarios. Natural gas provides valuable baseload capacity. Here’s why that matters.

Electricity demand is variable, both within the day and across the year. The amount of energy needed when the average temperature is 70 degrees is going to be far, far less than is required when it’s 30, or 90. It goes without saying that you want your furnace to work during a snowstorm, and your AC to keep things pleasant a summer heatwave. Similarly, energy demand within a day typically peaks in the evening, when people are at home and all their appliances are running.

However, most days aren’t going to be peak energy demand days, and most hours won’t be peak hours.

The output of renewables like solar and wind are also variable within the day and across the year. For solar, for example, the theoretical maximum output occurs on sunny days between 10:00 AM and 2:00 PM. After dark, you get minimum output – specifically, zero energy generated. Most of the time output will be somewhere between those two extremes. Ensuring sufficient renewable capacity to consistently meet peak demand would require far more solar panels, batteries and wind turbines than what would be needed for average generation requirements. Natural gas provides reliability supporting the energy needs across the country and ready to step in to prevent energy crises.

Furthermore, carbon capture and sequestration technologies have been mandated by the EPA for new power plants. With new natural gas power plants mandated to cut emissions 90% by 2030, the electricity provided by natural gas is likely to become even lower emissions over time, allowing the grid to lean even more on natural gas than it already does while continuing to lower emissions.

Taken all together, it’s no wonder that Princeton’s modeling now recognizes how invaluable natural gas will be to speeding decarbonization. The only remaining question is – why did it take until now for their modelling to identify this?